Delhi : In a bustling market in New Delhi, Priya, a young entrepreneur, sifted through a pile of affordable electronics and clothing, all stamped with the familiar label: “Made in China.” The prices were unbeatable—smartphones for a fraction of what they’d cost elsewhere, trendy clothes that rivaled high-end brands, and gadgets that promised cutting-edge technology at a bargain. “This is why China is winning,” she thought, echoing the sentiments of many in India who admired China’s economic prowess. But as she held a sleek phone in her hand, a question lingered: How could something so sophisticated be so cheap? The answer, buried beneath the shiny packaging, was a story of exploitation that would challenge her admiration for China’s success.

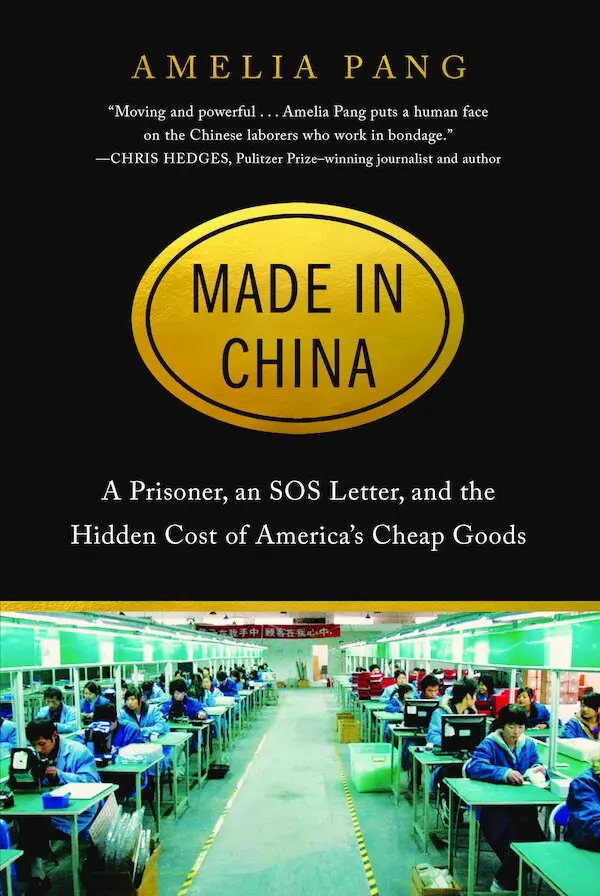

Across the border, in a sprawling factory in Shenzhen, China, 23-year-old Wei trudged through another 12-hour shift at an electronics assembly line. His hands moved mechanically, attaching components to circuit boards under harsh fluorescent lights. The air was thick with the smell of solder and chemicals, and the constant hum of machinery drowned out any chance of conversation. Wei was one of millions of Chinese workers fueling the global supply chain, producing the cheap goods that filled markets like Priya’s in India. But at what cost?

The Backbone of China’s Economic Miracle

China’s rise as the “world’s factory” is no accident. Its ability to produce vast quantities of affordable goods—electronics, textiles, toys, and more—has made it a global economic powerhouse. In 2023, China accounted for nearly 30% of global manufacturing output, exporting $3.6 trillion worth of goods. This success, however, rests on the backs of its workers, many of whom face grueling conditions that belie the country’s glossy image of progress.

Reports from organizations like China Labor Watch (CLW) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) paint a stark picture. Workers in China’s manufacturing hubs, such as the Pearl River Delta and Yangtze River Delta, often endure long hours, low wages, and unsafe conditions. A 2023 CLW report highlighted that workers in electronics factories faced “low basic salaries, excessive overtime, illegal use of student interns, hiring discrimination, and deception from labor brokers.” Many work 12- to 14-hour shifts, six or seven days a week, often without adequate breaks or overtime pay, in violation of China’s own labor laws, which stipulate a maximum of 8 hours per day and 44 hours per week.

Wei’s story is emblematic. A migrant from rural Hunan, he moved to Shenzhen seeking a better life. Instead, he found himself trapped in a cycle of exploitation. His monthly wage of 2,500 yuan (about $350 USD) barely covered his rent and food, forcing him to live in a cramped dormitory with eight others. Overtime was mandatory, and refusing it could cost him his job. “We are like oxen and horses,” Wei said, echoing a viral phrase used by Chinese workers on social media to describe their plight.

The Dark Side of Cheap Goods

The affordability of Chinese goods is directly tied to this labor model. Low wages and lax enforcement of labor laws allow manufacturers to keep production costs down, enabling companies like Shein, Temu, and global giants like Apple and Samsung to offer products at prices that dominate markets worldwide. For example, a 2024 report by the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre revealed that 83 major brands were implicated in supply chains linked to forced labor in Xinjiang, where Uyghur workers are coerced into factories under state-sponsored programs. These programs, often disguised as “poverty alleviation” or “vocational training,” involve transferring ethnic minorities to factories across China, where they face surveillance, restricted movement, and ideological indoctrination.

The use of forced labor is not limited to Xinjiang. Across China, factories rely on “dispatch labor” (workers hired through agencies) and student interns, who are often coerced into working long hours under the guise of educational programs. A 2020 U.S. Department of Labor report identified goods like textiles, electronics, and garments as being produced with forced labor, with supply chains extending to countries like Vietnam, where Chinese cotton is processed. This systemic exploitation ensures that the cost of production remains low, but it comes at a human cost that is rarely acknowledged by consumers marveling at bargain prices.

Back in Delhi, Priya’s friend Arjun, a labor rights activist, challenged her admiration for China’s economic model. “You’re praising their efficiency, but do you know what’s behind it?” he asked. He shared a report from China Labour Bulletin (CLB), which documented over 1,000 worker protests in 2023 alone, driven by unpaid wages, factory closures, and lack of severance pay. “These workers are treated as disposable. Is that the kind of progress we want to emulate?”

China’s Labor Laws: On Paper vs. Reality

China’s labor laws, on paper, appear robust. The Labor Contract Law of 2007 mandates written contracts, limits working hours, and ensures social insurance and severance pay. However, enforcement is weak. Local governments, keen on attracting investment, often turn a blind eye to violations to keep factories operational. The All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), the country’s only legal union, is government-controlled and prioritizes stability over worker advocacy. As a result, workers have little recourse to address grievances, and independent labor organizations face harassment or closure.

The lack of enforcement is compounded by cultural and systemic factors. The “wolf culture” in Chinese workplaces—characterized by intense pressure to conform and work overtime—discourages workers from speaking out. For migrant workers like Wei, the hukou system, which ties social benefits to one’s place of origin, further limits access to healthcare, education, and legal protections in urban areas. This creates a vulnerable workforce, easily exploited by employers and brokers.

The Ethical Question: Are Workers Less Than Human?

The exploitation of Chinese workers raises a profound ethical question: Are workers being treated as less than human? The answer lies in the conditions they endure. Reports describe workers subjected to dehumanizing practices—forced overtime, wage theft, hazardous environments, and even detention in dormitories. In Xinjiang, Uyghur workers face additional layers of oppression, including mass surveillance and forced cultural assimilation. These practices reduce workers to mere tools of production, their well-being sacrificed for profit.

This dehumanization is not accidental but systemic, driven by a global demand for cheap goods. Multinational corporations, while claiming to uphold labor standards, often benefit from lax oversight in China’s supply chains. For instance, a 2024 investigation by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism linked over 100 global brands to factories using forced labor, with products reaching markets as far as India. Consumers, including those in India, indirectly perpetuate this cycle by prioritizing low prices over ethical considerations.

Priya was shaken by Arjun’s revelations. She began to see the phone in her hand not as a triumph of innovation but as a product of human suffering. “If we keep buying these goods, are we complicit?” she asked. Arjun nodded. “We can’t change the system overnight, but we can start by asking questions and demanding transparency.”

Lessons for India

For Indians who admire China’s economic ascent, the reality of its labor practices serves as a cautionary tale. India, with its own aspirations to become a manufacturing hub, faces similar pressures to attract investment by keeping labor costs low. However, replicating China’s model risks repeating its mistakes. India’s labor laws, while imperfect, offer protections like the right to unionize and a stronger framework for collective bargaining. Yet, enforcement remains a challenge, and informal workers—over 90% of India’s workforce—often lack basic protections.

China’s experience highlights the need for India to prioritize worker rights as it expands manufacturing. Strengthening labor inspections, supporting independent unions, and ensuring transparency in supply chains can prevent the kind of exploitation seen in China. Moreover, Indian consumers can play a role by supporting ethical brands and advocating for fair trade practices. As Arjun told Priya, “We don’t have to choose between development and dignity. We can demand both.”

Resistance and Hope

Despite the grim reality, Chinese workers are not passive victims. Strikes and protests have surged, with workers using social media to document abuses and demand justice. Organizations like CLB and CLW amplify these voices, pushing for reform despite government crackdowns. In the electronics sector, workers have organized collective bargaining efforts, as seen in the 2014 Yue Yuen strike in Dongguan, where thousands demanded better wages and conditions. These acts of resistance show that workers are reclaiming their humanity, refusing to be reduced to “oxen and horses.”

For Wei, hope came in the form of a small labor NGO that helped him file a complaint against his employer for unpaid wages. Though the process was slow, it gave him a sense of agency. “I want to work, but I also want to be treated like a person,” he said. His story, and those of millions like him, is a reminder that behind every “Made in China” label is a human being deserving of respect.

A Call to Action

Back in Delhi, Priya decided to act. She began researching ethical alternatives to Chinese goods, supporting Indian brands that prioritized fair labor practices. She also shared her findings with friends, sparking conversations about the true cost of cheap products. “We can’t ignore this anymore,” she told Arjun. “If we want a better future, we have to start valuing workers—here and in China.”

The story of China’s workers is a wake-up call for India and the world. The cheap goods that flood global markets come at a steep human cost, one that challenges us to rethink our priorities. Do we want a world where workers are treated as less than human, their labor exploited for profit? Or do we strive for a system that balances economic progress with dignity? The choice lies not just with governments and corporations but with consumers like Priya, whose decisions can shape a more just future.

Resource :

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14747731.2016.1207934#d1e191

https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/against-their-will-the-situation-in-xinjiang

https://www.law.berkeley.edu/article/working-conditions-the-persistence-of-problems-in-chinas-factories/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14747731.2016.1207934

The hidden human costs linked to global supply chains in China

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-112jhrg76387/html/CHRG-112jhrg76387.htm

https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/workers-labor-rights-wages-oxen-horses-10022024163703.html