Secularism, as a cornerstone of modern democratic governance, emerged from the Enlightenment and was crystallized during the French Revolution with the principle that the state should remain neutral in matters of religion. This neutrality was intended to ensure equality and prevent the dominance of any single religious doctrine in public life. However, in recent decades, a growing body of leftist-liberal literature has challenged this framework, arguing that secularism inherently favors the majority culture and marginalizes minority religious identities. This shift has led to a paradoxical situation where leftist intellectuals, who have historically positioned themselves as champions of women’s liberation, now defend practices such as the burqa, niqab, Sharia law, polygamy, child marriage, halala, triple talaq, and female genital mutilation (FGM) under the guise of protecting minority rights. This article examines the contradictions within leftist-feminist activism, particularly the reluctance to critique practices within Islamic communities, and argues that this selective silence stems from a fear of cultural backlash and accusations of majoritarianism.

The Leftist Retreat from Secularism

The leftist critique of secularism rests on the assertion that a neutral state inherently perpetuates the dominance of the majority culture. For instance, scholars like Tariq Modood argue that secularism, by refusing to accommodate minority religious practices, effectively privileges the cultural norms of the majority, which are often secular or Christian in Western contexts (Modood, 2010). This perspective has gained traction in academic circles, with writers advocating for state intervention to provide “special opportunities” for minorities to preserve their religious identities. In practice, this has translated into support for policies that uphold practices such as wearing the burqa or niqab, implementing Sharia-based family laws, and tolerating cultural practices like polygamy and child marriage in minority communities.

However, this stance is not applied universally. Leftist intellectuals rarely advocate for similar accommodations in Islamic countries, where minority religious groups—such as Christians, Hindus, or Ahmadi Muslims—face systemic discrimination. For example, in Saudi Arabia, non-Muslims are prohibited from practicing their faith publicly, yet leftist critiques of such policies are conspicuously muted compared to their vocal defense of Muslim minority practices in Western democracies. This selective advocacy reveals a double standard, where the principles of equality and secularism are subordinated to a hierarchy of cultural sensitivities.

Leftist-Feminist Hypocrisy: Liberation for Some, Silence for Others

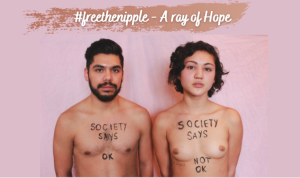

Leftist-feminist movements have been at the forefront of challenging patriarchal norms, with campaigns like “Free the Nipple” in the United States and the “Pink Chaddi” movement in India. The former seeks to destigmatize female nudity and challenge gendered double standards in public spaces, while the latter protested moral policing by sending pink underwear to conservative groups in 2009. These campaigns, bold and confrontational, embody the leftist commitment to dismantling oppressive structures and empowering women to assert control over their bodies.Yet, when it comes to practices within Islamic communities, the same fervor is conspicuously absent. The burqa and niqab, which cover women’s faces and bodies entirely, are often defended by leftists as expressions of cultural identity or personal choice, despite their roots in patriarchal interpretations of modesty. Similarly, practices like triple talaq (instant divorce by a husband pronouncing “talaq” three times), halala (requiring a divorced woman to marry another man and consummate the marriage before remarrying her original husband), and FGM are rarely critiqued with the same intensity as majority cultural practices. For instance, in 2017, when India’s Supreme Court declared triple talaq unconstitutional, some leftist intellectuals framed the ruling as an attack on Muslim identity rather than a victory for Muslim women’s rights (Hasan, 2017).

This reluctance to engage critically with Islamic practices stands in stark contrast to the boldness of campaigns like “Free the Nipple.” The fear of being labeled Islamophobic or of provoking violent backlash—epitomized by slogans like “sar tan se juda” (behead those who insult Islam), which have been chanted in protests against perceived blasphemy—appears to paralyze leftist-feminist activism. For example, in 2015, when French magazine Charlie Hebdowas attacked for publishing cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, some leftist commentators, while condemning the violence, criticized the magazine for “provoking” Muslim sentiments, effectively shifting blame from the perpetrators to the victims (Fassin, 2015). This hesitation to challenge Islamic practices contrasts sharply with the fearless critique of Hindu or Christian patriarchal norms, such as sati or restrictive abortion laws.

This reluctance to engage critically with Islamic practices stands in stark contrast to the boldness of campaigns like “Free the Nipple.” The fear of being labeled Islamophobic or of provoking violent backlash—epitomized by slogans like “sar tan se juda” (behead those who insult Islam), which have been chanted in protests against perceived blasphemy—appears to paralyze leftist-feminist activism. For example, in 2015, when French magazine Charlie Hebdowas attacked for publishing cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, some leftist commentators, while condemning the violence, criticized the magazine for “provoking” Muslim sentiments, effectively shifting blame from the perpetrators to the victims (Fassin, 2015). This hesitation to challenge Islamic practices contrasts sharply with the fearless critique of Hindu or Christian patriarchal norms, such as sati or restrictive abortion laws.

Case Studies: The Burqa, Sharia, and Child Marriage

To illustrate the leftist double standard, consider the burqa and niqab. In France, the 2010 ban on face-covering garments was met with fierce opposition from leftist intellectuals, who argued that it infringed on Muslim women’s freedom of expression. Yet, feminist scholars like Leila Ahmed have noted that these garments are often imposed by familial or communal pressures, not chosen freely (Ahmed, 2011). The leftist defense of the burqa as “empowering” ignores the lived realities of women in countries like Afghanistan, where the Taliban’s 2022 mandate requiring full-body coverings was met with minimal criticism from Western leftists.

Similarly, the endorsement of Sharia-based family laws in minority communities reflects a troubling oversight. In the United Kingdom, Sharia councils have been criticized for issuing rulings that discriminate against women, such as denying alimony or enforcing unequal inheritance (Casey, 2016). Yet, leftist advocates like John Esposito argue that such councils are essential for preserving Muslim identity, downplaying their impact on gender equality (Esposito, 2011). This contrasts with the vocal leftist opposition to Christian-influenced laws, such as those restricting reproductive rights in the United States.

Child marriage, another practice defended under the banner of cultural relativism, is particularly egregious. In countries like Bangladesh, where the legal marriage age for girls was lowered to 16 in 2017 with parental consent, leftist silence is deafening, despite UNICEF data showing that child marriage perpetuates cycles of poverty and gender inequality (UNICEF, 2018). The same leftists who campaign against child marriage in Hindu or Christian communities often refrain from critiquing similar practices in Muslim-majority contexts, citing cultural sensitivity.

The Fear Factor: “Sar Tan Se Juda” and Leftist Silence

The leftist reluctance to critique Islamic practices is not merely a matter of ideological inconsistency but also of fear. The slogan “sar tan se juda,” associated with violent protests against perceived insults to Islam, encapsulates the threat of retribution that looms over critics. High-profile cases, such as the 2022 murder of Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh for his film Submission, which critiqued the treatment of women in Islam, serve as stark reminders of the risks involved. This fear has led to a chilling effect, where leftist-feminists avoid campaigns like “Free the Nipple” in Muslim communities, lest they be accused of blasphemy or cultural insensitivity.This selective silence undermines the universalist principles of feminism. By prioritizing cultural relativism over women’s rights, leftists inadvertently reinforce the very patriarchal structures they claim to oppose. The embarrassment of campaigns like “Free the Nipple” in the face of Islamic practices highlights a deeper cowardice: the fear of confronting a minority community’s practices, even when they contradict the leftist commitment to gender equality.

The leftist-liberal retreat from secularism and selective feminist activism represent a betrayal of the principles of universal human rights. By defending practices like the burqa, Sharia, and child marriage in the name of minority rights, leftists undermine their own advocacy for women’s liberation. The fear of backlash, epitomized by slogans like “sar tan se juda,” has created a double standard that embarrasses campaigns like “Free the Nipple” and exposes the hypocrisy of leftist-feminist discourse. A return to secularism, coupled with a consistent application of feminist principles across all communities, is essential to reclaiming the integrity of the fight for gender equality.

References

- Ahmed, L. (2011). A Quiet Revolution: The Veil’s Resurgence. Yale University Press.

- Casey, L. (2016). The Casey Review: A Review into Opportunity and Integration. UK Government.

- Esposito, J. (2011). What Everyone Needs to Know About Islam. Oxford University Press.

- Fassin, E. (2015). “In the Name of the Republic.” Anthropology Today, 31(2), 3-7.

- Hasan, Z. (2017). “Triple Talaq and the Politics of Gender.” Economic and Political Weekly, 52(35).

- Modood, T. (2010). Multiculturalism: A Civic Idea. Polity Press.

- UNICEF. (2018). Child Marriage: Latest Trends and Future Prospects. UNICEF Data.