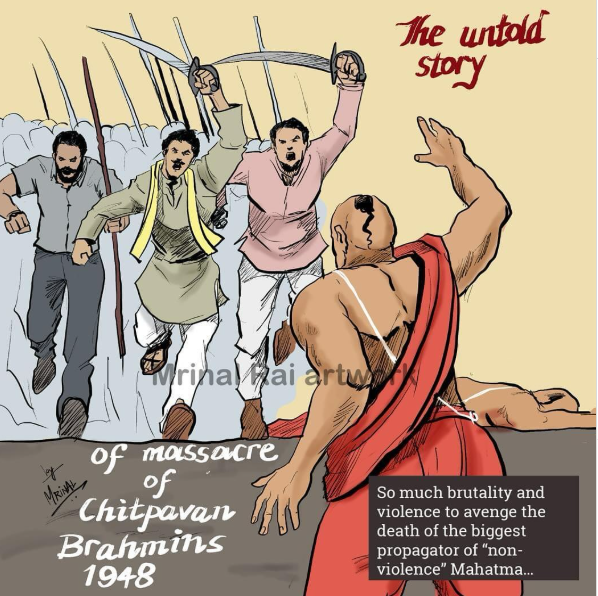

The spark was Godse’s act. A man driven by his own convictions, he pulled the trigger, believing Gandhi’s policies had weakened India. But his bullet did more than end a life—it unleashed a tsunami of vengeance that swept across Maharashtra. Within hours, the news of Gandhi’s death reached the towns and villages of Pune, Satara, Kolhapur, and beyond. Mobs, armed with kerosene cans, iron rods, and machetes, descended upon Brahmin neighborhoods. They weren’t just angry; they were organized, fueled by a venomous narrative that painted every Chitpavan Brahmin as complicit in Gandhi’s murder. The streets turned into a slaughterhouse. Homes were torched, their inhabitants dragged out and butchered. Women were raped, children hacked to pieces, and entire families erased in a frenzy of violence that lasted for days. In Satara alone, over 1,000 homes were reduced to ashes, their owners either dead or fleeing for their lives. The unofficial death toll, as whispered by survivors and later documented by a few brave voices, ranged from 5,000 to 8,000—numbers so staggering they defy comprehension.

The horror was not random. It was a meticulously planned pogrom. In an era without social media or even widespread telephone access, how did mobs across Maharashtra know exactly where Chitpavan Brahmins lived? How did they assemble so swiftly, armed with weapons and fueled by a unified hatred? The answer lies in the complicity of those in power. Congress workers, alongside local Maratha, Jain, and Lingayat groups, were reported to have led the charge. Dwarka Prasad Mishra, a senior Congress leader, later admitted in his memoirs to the involvement of Congressmen in the violence, describing it with chilling nonchalance. Lorries owned by Congress supporters ferried mobs to Brahmin homes, ensuring no corner of Maharashtra was spared. The police, overwhelmed or unwilling, stood by as the carnage unfolded. In Nagpur, when fire brigades arrived to douse the flames engulfing Brahmin properties, mobs forced them to retreat. The state machinery, under the watchful eye of Nehru’s Congress, either turned a blind eye or actively facilitated the slaughter

The Chitpavan Brahmins were no ordinary community. They were the backbone of the Maratha Empire, the Peshwas who had once challenged Mughal and British rule. Leaders like Lokmanya Tilak, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, and Veer Savarkar hailed from their ranks, their names synonymous with India’s fight for freedom. Yet, their prominence made them targets. Historical rivalries with other castes, particularly the Marathas, simmered beneath the surface, and Gandhi’s assassination provided the perfect pretext to settle old scores. The mobs didn’t just target those named Godse; they attacked anyone with a Brahmin surname, anyone who bore the mark of Chitpavan identity. In Kolhapur, the studio of renowned filmmaker Bhalji Pendharkar, a Karhade Brahmin, was reduced to rubble. In Satara, Arvind Kolhatkar, a survivor, recounted how his family’s printing press and typewriter were destroyed, ensuring they could neither read nor write if they survived. The violence was not just about killing—it was about erasing a community’s legacy, their voice, their very existence

What makes this massacre even more chilling is the silence that followed. The Indian media, under the sway of the Congress government, barely whispered about the atrocities. While foreign newspapers like The New York Times reported initial killings in Bombay—15 on the first day alone—the Indian press remained eerily mute. The Times of India and Hindustan Times, giants of the era, focused on Gandhi’s martyrdom and national mourning, relegating the Brahmin massacre to obscurity. Editorials called for unity and peace, but none dared to confront the bloodbath in Maharashtra. This was no accident. The Congress government, keen to consolidate power in a fractious new nation, had every reason to suppress a narrative that exposed its complicity. Historians like Maureen L.B. Patterson, researching decades later, were denied access to police files on the 1948 riots, a clear sign of a deliberate cover-up. The voices of the victims—those who lost homes, loved ones, and livelihoods—were silenced, their pain buried under the weight of a sanitized national narrative.

The irony is suffocating. Gandhi, who preached non-violence, became the catalyst for a massacre carried out in his name. His followers, the so-called Gandhians, betrayed his ideals by wielding machetes and torches against innocent Brahmins. Nehru, the architect of modern India, stood at the helm as his party’s workers orchestrated a genocide that rivaled the horrors of partition. The same Congress that condemned Godse as a terrorist turned a blind eye to the terror it unleashed. And the media, which today some call “Godi” for its perceived subservience to power, was no different then. Under Congress’s influence, it buried the truth, ensuring that the first massacre of independent India remained a forgotten footnote. The term “Godi media” may be modern, but the phenomenon of a pliant press was born in those blood-soaked days of 1948.

Among the most heart-wrenching stories is that of Veer Savarkar’s family. Savarkar, a towering figure in the Hindu nationalist movement, was falsely implicated as a co-conspirator in Gandhi’s murder. His brother, Narayan Rao Savarkar, was stoned to death by a mob in Pune, his body left to rot as a warning to others. The Savarkar family’s properties were looted and burned, their legacy desecrated. Across Maharashtra, Brahmin families faced similar fates. In Aundh, the violence spanned 300 districts, with entire villages razed. Women were violated in the streets, their screams drowned out by the roar of flames. Children, too young to understand caste or politics, were cut down without mercy. The survivors, those who fled with nothing but the clothes on their backs, carried scars that would never heal. They became refugees in their own land, their dreams of a free India shattered by the very forces that claimed to build it.

The massacre’s scale is staggering, yet its erasure is even more so. Official records are scarce, and estimates of the death toll vary widely, from 1,000 to 8,000. The lack of documentation is no accident; it is the hallmark of a state intent on rewriting history. While the 1984 anti-Sikh riots are rightly remembered as a national tragedy, the 1948 Brahmin massacre remains shrouded in silence. No justice was served, no perpetrators punished. The Congress government, quick to canonize Gandhi as a martyr, ensured that the blood of thousands of Brahmins would never stain its legacy. Even today, political leaders in Maharashtra exploit anti-Brahmin sentiment for votes, a grim echo of the hatred that fueled the pogrom.

This is the untold story of independent India’s first massacre-a tale of betrayal, bloodshed, and a cover-up so complete that it haunts the nation’s conscience. The Chitpavan Brahmins paid the ultimate price for one man’s act, their suffering erased to protect the myth of a peaceful transition to independence. The Gandhians and Nehruvians, cloaked in the rhetoric of non-violence and secularism, orchestrated a genocide that exposed the fragility of their ideals. As the flames of 1948 died down, they left behind not just ashes, but a wound that festers in silence, a reminder that even in a free India, some truths are too horrific to be told.

Reference :

https://www.firstpost.com/opinion/how-nehruvian-congress-manipulated-mahatma-gandhis-assassination-to-emasculate-hindu-nationalism-10961811.html

The untold story of the massacre of 5000 Chitpavan Brahmins by Congress goons

The Brahmin Files: Independent India’s First Political Genocide