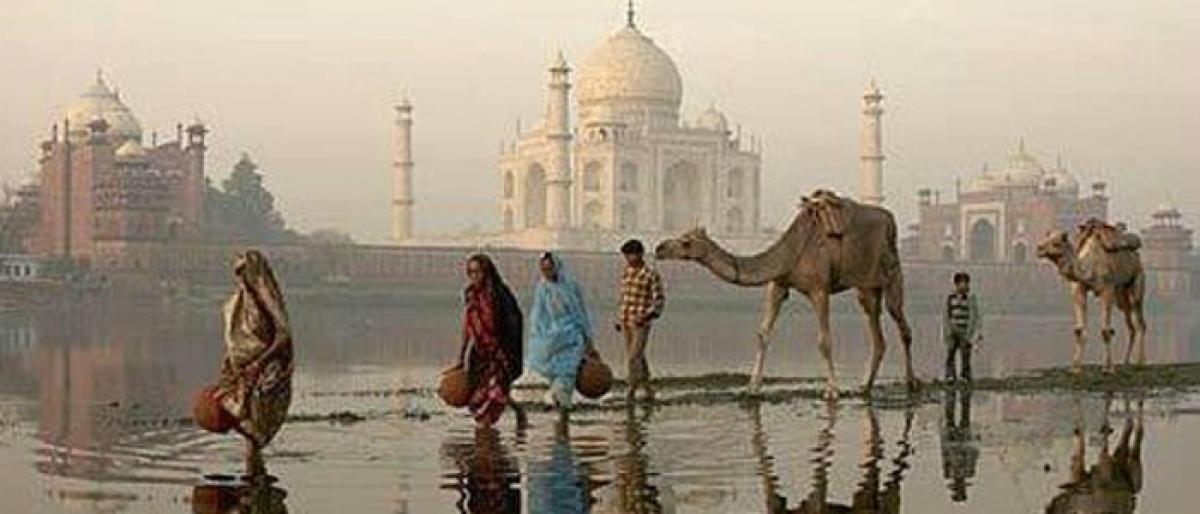

Agra, immortalized by the gleaming white marble of the Taj Mahal, today stands as a horrifying paradox. While its monuments tell tales of love and grandeur, the streets throb with turbulent chaos. What went wrong? This question lingers in the air, muffled by traffic congestion, dwindling greenery, and crumbling infrastructure. At the center of this turmoil are a number of government bodies: the TTZ, the Agra Development Authority (ADA), the Agra Municipal Corporation, Awas Vikas, the Zila Panchayat, and the Tourism Department. Together, over the past fifty years, they have replaced vision with negligence and tradition with profit.

Famous for its rich cultural fabric, Agra has been a victim of poor political leadership and ad hoc planning. As urban sprawl engulfs Agra’s historicity and expanding colonies replace greenery, one must ask: what is the role of the state machinery in this growing disaster?

When we peel away the layers of neglect, contradictory policies, and uninspired vision of this magnificent city, the truth emerges in a horrifying way: Agra’s chaos is a direct reflection of the incompetence or unwillingness of its city planners. This approach poses a major challenge not just to the city’s architecture but also to its soul. In this exploration, we confront the uncomfortable realities of urban development, questioning whether Agra is still capable of rising from the ashes of mismanagement or whether it is destined to remain in the shadow of its glory.

The Agra Development Authority has invested 50 years to bring Agra to where it is today. City dwellers, bored or disenchanted with spurious development, are now dreaming of a Ssmart city.

Some argue that the failure or directionlessness of the ADA has pushed the city into a trough of problems. Traffic congestion, filth, broken roads, and lack of basic amenities have made Agra an unlivable city.

Agra’s urban plight is a reminder of the deeper problems that plague many cities in India. Despite collecting tolls from tourists visiting this international tourist city, the efforts of the authority to streamline facilities remain lackluster, leaving residents frustrated and the underprivileged forced to live without basic necessities.

Citizens say that the ADA has not been able to build a single sports stadium. In nearly half a century of its existence, the ADA has not built any public park, recreation center, public swimming pool, art gallery, community marriage hall, exhibition ground, shopping complex, tourist waiting room, or classy public toilets.

Citizens say that two of the ADA’s grand projects are Sanjay Place Market and Shastripuram Colony. This rainy season, we saw the high-class arrangements of the town planning department, while the entire colony remained submerged in deep water for several days. The less said about Sanjay Place, the better. When the Central Jail was shifted in 1976, the ADA was given this huge chunk of land in the heart of the city and we all thought that something like Connaught Circus would be built here. Social activist Dr. Rajan Kishore predicted then that it would become Kinari Bazaar in the future. “The first thing the ADA did was level the huge pond to allow the LIC to build its regional office there. On the other hand, the Wazirpura Crossing pond also disappeared,” recalls an elderly man.

With a population of over 20 lakh residents, Agra has become a mix of rich cultural heritage and modern challenges. Instead of prioritizing the welfare of all residents and investing in sustainable urban development, the ADA perpetuates an elitist bias that neglects the needs of marginalized communities.

The call to revamp this government institution and place it under the jurisdiction of a democratically elected municipal corporation is an important step towards addressing the aspirations of the public and moving the city towards inclusive growth. By transferring power from bureaucrats to elected representatives, the governance structure can become more accountable and responsive to the needs of the people. This change is necessary to ensure that urban planning and development in Agra reflect the voices and concerns of all residents, especially those living in deprived areas.

People often ask, “When you already have the municipal corporation and its smart city company, what kind of development is the ADA engaged in?”

Recently, a gynecologist who visited from Chennai shared her disappointment, saying, “I thought Agra would be wonderful because of the Taj Mahal, but the dirt, broken roads, and garbage everywhere were unbearable.”

Officials often cite lack of resources as the main reason for their inefficiency. However, in the last few years, the authority has earned significant revenue from historical monuments and tourist toll tax. “Where all this money has been spent, only God knows, because you don’t see the results,” says a local resident.

Agra earns more money from tourism than any other city in India, but in return, the ADA has not given the region its due. The city’s roads, public amenities, cleanliness, street lighting, and local transport facilities are neglected.

Indeed, Agra’s chaos is a direct reflection of its town planners’ inability or unwillingness to see beyond their immediate mandates. The negligence sanctioned by the ADA poses a stark challenge, not just to the city’s architecture, but to its soul. In this exploration, we confront the uncomfortable realities of urban development, questioning whether Agra is still capable of rising from the ashes of mismanagement, or if it is destined to live under the shadow of its own glories.