The Suppressed Sting of 2008: The Cash-for-Votes Scandal

On July 22, 2008, the Indian Parliament was abuzz with a no-confidence motion against the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government, led by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, over the controversial Indo-US nuclear deal. The deal, signed between Singh and US President George W. Bush, was hailed as a landmark for India’s energy needs but faced fierce opposition from the Left and the BJP, who labeled it a compromise of India’s strategic autonomy. As the nation awaited the confidence vote, a major news channel teased a sensational sting operation, promising to expose how MPs were allegedly bought to secure votes for the UPA. Promos aired throughout the day, building anticipation. Yet, as the clock ticked past the scheduled broadcast time, the sting never aired. The story was effectively “murdered,” as Manoj Maniyanil notes in his posts.

The channel in question was CNN-IBN, then led by editor-in-chief Rajdeep Sardesai. According to Maniyanil, the decision to suppress the sting operation, which allegedly revealed a “cash-for-votes” scandal, shielded the UPA government from potentially damning scrutiny. This incident raises uncomfortable questions: Why was such a critical exposé buried? Was it a case of editorial caution, or did external pressures influence the decision? Today, Sardesai is among those who critique media houses for selective reporting, yet his role in this episode suggests a selective memory when it comes to journalistic accountability

The Niira Radia Tapes: Lobbying in the Corridors of Power

Fast forward to 2010, when the Niira Radia tapes scandal rocked the Indian media. The leaked telephone conversations, recorded by the Income Tax Department in 2008–09, revealed political lobbyist Niira Radia engaging with senior journalists, politicians, and corporate figures. Among those implicated were prominent journalists like Barkha Dutt, then with NDTV, and Prabhu Chawla, former editor of India Today. The tapes suggested that some journalists were not merely reporting news but actively lobbying for corporate interests, including influencing the appointment of A. Raja as Telecom Minister in the UPA cabinet—a decision linked to the infamous 2G spectrum scam.

On November 30, 2010, Barkha Dutt appeared on NDTV to address the controversy, flanked by a panel of senior journalists. She admitted to an “error of judgment” in her conversations with Radia but denied any wrongdoing, insisting she never lobbied for Raja, whom she claimed she had consistently criticized in her reporting. Prabhu Chawla, similarly entangled, faced less public scrutiny but was also implicated in casual discussions with Radia. Rajdeep Sardesai, writing in the Hindustan Times, lamented that the “robust Indian tradition of adversarial journalism has been mortgaged at the altar of cozy networks.” Yet, the irony is stark: journalists who were part of such networks now position themselves as moral arbiters, calling out media houses for biased reporting while sidestepping their own past

Manmohan Singh’s Editor’s Meet: A Tame Narrative

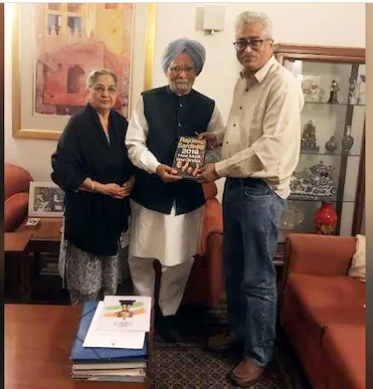

On June 29, 2011, amidst a slew of scams—2G, Commonwealth, and coal—Prime Minister Manmohan Singh met with a select group of editors for a two-hour discussion. At the time, the UPA government was under fire, and public outrage was mounting over corruption. Yet, the headline that emerged from this meeting was tame: Singh expressed his willingness to come under the purview of the Lokpal, an anti-corruption ombudsman proposed to address systemic graft. This carefully curated narrative deflected attention from the government’s failures and focused on a reformist gesture. The editors present, some of whom are vocal critics of “Godi Media” today, appeared complicit in amplifying this distraction rather than pressing Singh on the scams plaguing his government.

The Hypocrisy of the “Godi Media” Critique

The term “Godi Media” gained traction in 2018, popularized by Ravish Kumar to describe media outlets perceived as subservient to the BJP government. Rajdeep Sardesai himself has used the term “lapdog media” to critique the current media landscape, stating, “A large section of the Indian media has become a lap dog, not a watchdog.” Yet, the incidents of 2008–2011 reveal that journalistic compromises are not a new phenomenon, nor are they exclusive to one political regime. The suppression of the cash-for-votes sting, the lobbying exposed by the Radia tapes, and the sanitized coverage of Singh’s editor’s meet suggest that cozy relationships between journalists and power structures predate the Modi era.

Manoj Maniyanil’s social media posts serve as a reminder that those who decry “Godi Media” today were, in some cases, beneficiaries of the UPA’s patronage. Rajdeep Sardesai, Barkha Dutt, and others received prestigious awards like the Padma Shri during the UPA’s tenure, raising questions about whether such honors were tied to their alignment with the government. Moreover, the accusation that NDTV, where Dutt and Kumar worked, was ‘born and brought up in the lap of UPA PM Dr. Manmohan Singh’ further complicates the narrative of journalistic purity.

A Call for Introspection

The irony is inescapable: journalists who once navigated murky ethical waters now lecture others on media ethics. Rajdeep Sardesai’s suspension from India Today in 2021 for spreading misinformation about a farmer’s death during the Republic Day protests highlights that lapses in judgment persist. Similarly, Barkha Dutt’s defense of her actions in the Radia tapes scandal as a mere “error of judgment” underscores a reluctance to fully confront past mistakes.

As we debate “Godi Media” today, we must ask: Which era of journalism are we glorifying? The one where stings were suppressed to protect a government? Or where journalists played power brokers? The Indian media’s credibility crisis is not new—it is a legacy of compromises that spans regimes. To move forward, journalists must embrace introspection over selective outrage, ensuring that the watchdog doesn’t become a lapdog, regardless of who holds power.