The Rohith Vemula Act, aimed at addressing discrimination in educational institutions, raises several constitutional concerns that could lead to its invalidation if challenged in the Supreme Court of India.

Delhi : The proposed Rohith Vemula Act, aimed at addressing discrimination in educational institutions, particularly against Dalit, Adivasi, OBC, and minority students, has sparked heated debate. While its intent to curb systemic prejudice is noble, the Act’s provisions, as discussed in recent public discourse, raise serious constitutional concerns that make it vulnerable to being struck down if challenged in the Supreme Court. Nationalist activists and lawyers must step forward to scrutinize this legislation, ensuring it aligns with India’s constitutional framework.

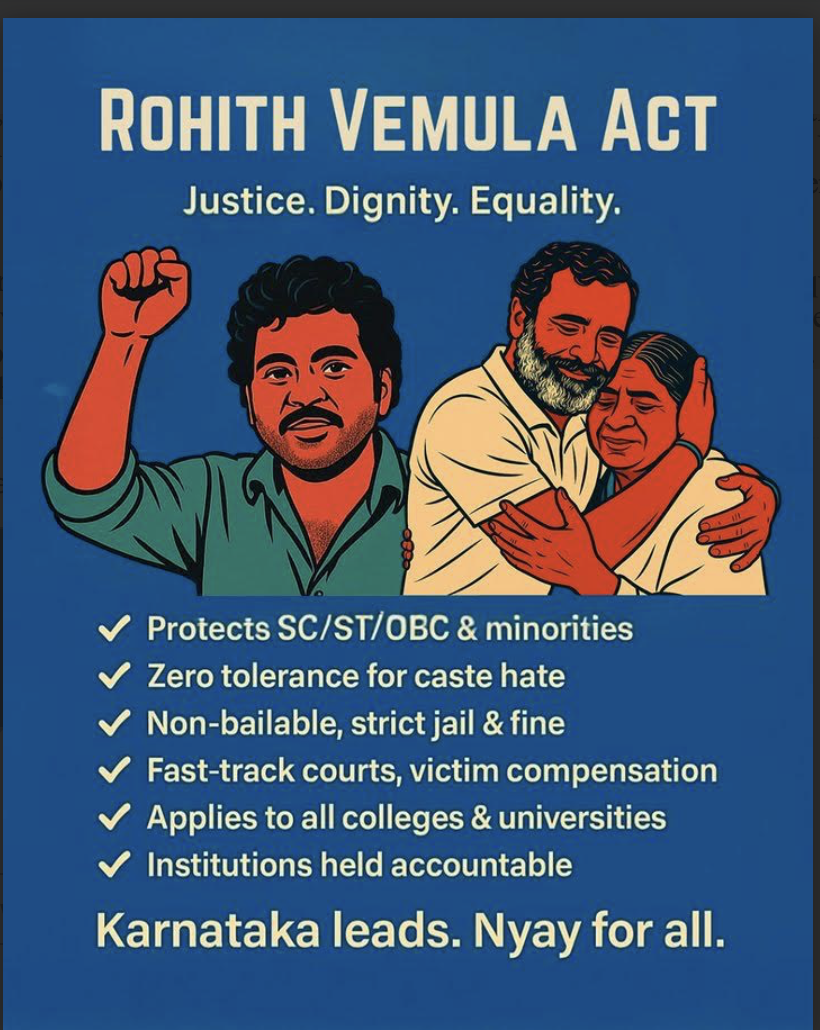

The Act, reportedly backed by Congress-led state governments in Karnataka, Telangana, and Himachal Pradesh, introduces stringent measures like non-bailable and cognizable offenses, allowing arrests without preliminary inquiries. It also imposes college liability, bystander punishment, and pre-conviction payouts of ₹1 lakh. These provisions, while designed to deter discrimination, risk violating fundamental principles of justice, particularly the right to due process enshrined in Article 21 of the Constitution. The Supreme Court has consistently struck down laws that undermine procedural fairness, as seen in cases like Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978), which emphasized the need for laws to be just, fair, and reasonable.

The Act’s broad scope, extending to OBCs and minorities alongside SC/ST communities, overlaps with the existing SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, creating redundancy and potential misuse. Social media discussions, particularly on platforms like X, highlight concerns that the Act institutionalizes bias under the guise of justice, potentially discriminating against general-category individuals. Such provisions could infringe on Article 14’s guarantee of equality before the law, as they risk creating unequal treatment based on caste or community. The Supreme Court’s ruling in Gambirdhan Gadhvi v. State of Gujarat (2022) underscores that laws violating union supremacy on concurrent list subjects, like education, are constitutionally suspect, further weakening the Act’s legal standing.

Moreover, the Act’s punitive measures, such as pre-conviction payouts and bystander liability, may contravene the principle of “innocent until proven guilty,” a cornerstone of Indian jurisprudence. The Court’s history of invalidating draconian laws, like portions of the UAPA or PMLA when deemed excessive, suggests that these provisions may not withstand judicial review. The Act’s vague definitions of discrimination could also lead to arbitrary enforcement, inviting challenges under Article 19 for restricting free speech and association.

Nationalist activists and lawyers must challenge this Act in the Supreme Court to safeguard constitutional principles. By ensuring laws balance justice with fairness, they can prevent well-intentioned but flawed legislation from fostering division or injustice. The judiciary’s role as a constitutional check demands such vigilance to uphold India’s legal integrity.

Below is a detailed explanation of these concerns, rooted in constitutional principles and judicial precedents:

Bullet Points :

Violation of Article 21 (Right to Life and Personal Liberty):

The Act’s provisions, such as non-bailable and cognizable offenses allowing arrests without preliminary inquiries, risk undermining due process. Article 21 guarantees that no person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty except through a procedure established by law, which must be just, fair, and reasonable, as established in Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978). The Act’s pre-conviction payouts and bystander liability provisions could be seen as punitive without adequate proof of guilt, violating the principle of “innocent until proven guilty.” The Supreme Court has struck down laws or provisions that bypass procedural fairness, as seen in cases like Kartar Singh v. State of Punjab (1994), where excessive police powers were curtailed.

Violation of Article 14 (Right to Equality):

The Act’s expansive scope, covering SC/ST, OBC, and minority students, may create unequal treatment by implicitly excluding general-category individuals from similar protections. Article 14 mandates equality before the law and equal protection of laws. Laws that create differential treatment without a reasonable classification or nexus to the objective risk being struck down, as seen in State of West Bengal v. Anwar Ali Sarkar (1952). Social media discussions on platforms like X suggest the Act could be perceived as institutionalizing bias against certain groups, further weakening its constitutional validity.

Overlap with Existing Laws and Federal Structure Concerns:

The Act overlaps with the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, which already addresses caste-based discrimination. This redundancy raises questions about its necessity and risks overreach into Union legislative powers, as education is a concurrent list subject under the Seventh Schedule. The Supreme Court, in Gambirdhan Gadhvi v. State of Gujarat (2022), emphasized that state laws encroaching on Union supremacy in concurrent subjects are vulnerable. The Act’s state-driven approach may conflict with central laws, inviting judicial scrutiny.

Potential Infringement on Article 19 (Fundamental Freedoms):

The Act’s vague definitions of discrimination could restrict freedom of speech and association under Article 19(1)(a) and (c). For instance, broad interpretations of discriminatory acts might penalize legitimate academic or social interactions, chilling free expression. The Supreme Court, in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015), struck down Section 66A of the IT Act for vagueness, setting a precedent for invalidating ambiguous laws that curb fundamental rights.

Excessive and Arbitrary Provisions:

Provisions like college liability and bystander punishment may be deemed disproportionate, failing the test of reasonableness under Article 14 and 21. The Supreme Court has invalidated overly harsh measures, such as in Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017), where privacy-invasive laws were curtailed. The Act’s pre-conviction payouts lack judicial oversight, risking arbitrary enforcement and misuse, which the Court has historically opposed.

The Rohith Vemula Act’s provisions clash with constitutional guarantees of due process, equality, and fundamental freedoms, while its overlap with existing laws and potential federal overreach further weaken its legal standing. These concerns make it ripe for challenge in the Supreme Court, where judicial precedents favor striking down laws that fail to balance justice with constitutional integrity. Nationalist activists and lawyers should scrutinize these issues to ensure the Act aligns with India’s constitutional framework.