MS Desk

The status of a ‘family’ has been considered a unit for conferring Reservation benefits in this Report, as it is a family which is forward or backward, rich or poor, educated or uneducated, all of which directly impact a person. Those families who fulfil all the above criteria should be given priority.

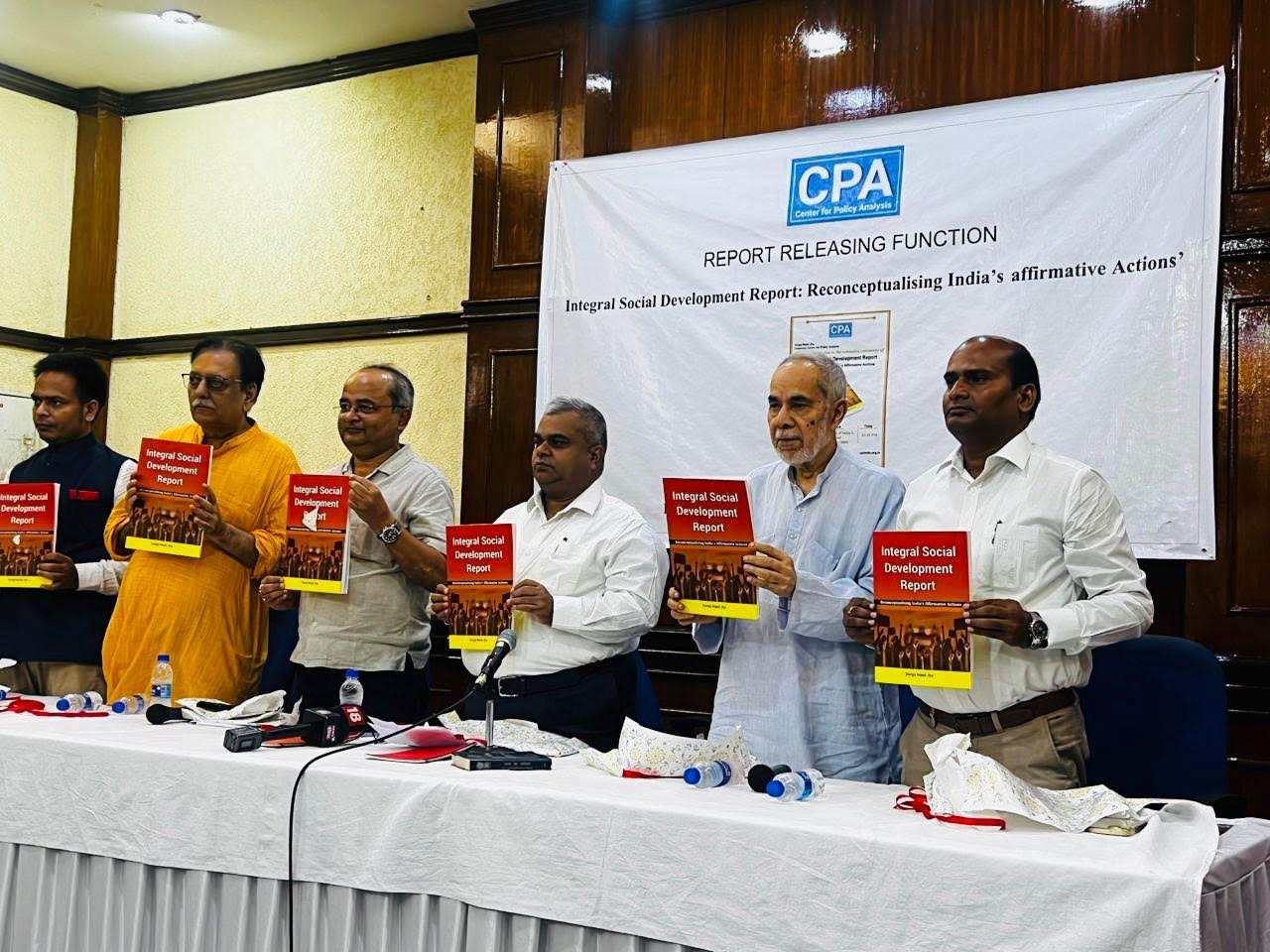

1. Fundamental thrust of ‘The Integral Social Development Report: Reconceptualising India’s affirmative Actions’ (ISDR) is that the fresh thinking and new approach are required to view India’s Affirmative Actions, in order to make it futuristic and reflective to the new realities of India.

2. The approach of this report is conceptually analytical, and curative as it examines the ideational basis that underpins India’s Affirmative Actions in general, and the Report of the Second Backward Classes Commission in particular, and recommends a set of solutions which intends to banish anomalies of the current policy.

3. The actualisation of ‘social justice’ is relevant in the context of Scheduled Castes as they had to face certain kinds of discrimination. That is why the narrative of ‘social justice’ is a misnomer in the context of backward castes as the backwardness is associated with low developmental attainment. The case of Scheduled Castes is low developmental attainment plus social discrimination, whereas the case of OBCs is limited only to the low developmental attainment. The case of the both is circumstantially different, hence they cannot be equated with each other.

4. In the last three decades, Indian society has witnessed a complete transformation. As a result, there is no caste in which all persons are backward. This was the fundamental assumption on the basis of which caste and class was equated; but now, this has lost its validity. The (ISDR) debunks the fundamental assumption of the Report of the Second Backward Classes Commission that ‘caste is a class’.

5. Caste as a group indicator of backwardness is invalid in the current situation. Hence, the policy and programs based on this assumption do not hold validity any longer.

6. The policies that were designed for the India in the pre-economic reform period are in no way appropriate in today’s changed scenario as they are not supportive of the current aims and ambitions of the country. The transformation which has taken place in India in the first quarter of this century has completely transformed the social, economic and educational attainment status of the country.

7. The ongoing Affirmative Action policies of the government, in their present form, are in the interest of all who have been categorised as backwards. As has been seen, these are abnormally favourable to a few dominant castes, and dismally unfavourable to the most backward castes of the group.

8. If a section of society is faring well on its own, it needs the appropriate appreciation of society for their labour and talent. They are not villains of society. If a country becomes hostile towards its creative, talented, and hard-working people, it is neither in the interest of the country nor in the interest of the persons who have left behind, since it is they who indirectly fund — being the main contributory to the coffers of the country— the Affirmative Action policies of the government.

9. It is important to understand that policies should not be framed in a way that the social diversity of the country turns into its ‘social fault lines’ and increases its vulnerability.

10. The social sub streaming of any kind should not be given much importance in policy framework as it hampers the attainment of the objective of the ‘mainstreaming of various social groups’ by weakening a sense of common purpose in society.

11. ‘jis ki jitni sankhya bhari, uski utni hissedari’. When this kind of number centric assertion is made, it no more remains an issue of inclusiveness. Similarly, it also ceases to be an affirmative actions. This kind of assertion implies that the percentage of caste in the total population of the state should be recognised as one of the most important determining factors for appointment in public office. The demand for the distribution of opportunities in various government offices and public institutions, as per the vastness of the size of the caste, put this policy in a category of ration scheme of Public Distribution System, in which quantum of grain to be given is decided as per the size of a family. This is moral and ideational degradation of the basis on which Affirmative Actions are justified. The problem is that the votaries of such demand are unable to make a distinction between two altogether different programmes.

12. The public policies of the government should not ignore the interests of the common people. It is important to see that the quality of the public services, of which the common people are the main recipients —irrespective of caste, class and religion and gender — should not get affected because of misplaced perceptions of the Affirmative Actions.

13. The linking of the incidence of backwardness with caste identity, changed the nature of the issue from being an economic and educational one to a social one.

14. The people of the rural areas are developmentally in a more disadvantageous situation than the people in urban areas. Therefore, it is the call of justice that the more appropriate and bigger indicators and locators of backwardness should get preference over caste identity.

15. It is an indisputable fact that, on almost all parameters of development, the urban-rural divide is much sharper than the development gap between two group of castes.

16. Everybody is fighting to join the queue of backwards, no one wants to remain bereft of the badge of backwardness. At the moment, the biggest challenge is: how does one disincentivize the badge of backwardness?

17. There is a need to break the vicious circle of the backwardness. The present way of conferring benefits of the Affirmative Actions policy nourishes it.

18. A backward State will always remain backward because of its policies that cherishes the backwardness of its people. The spirit of the Article 335 of the Indian Constitution must be kept in mind by the governments.

19. Ram Manohar Lohia, had pointed out that this could be a possibility, which later would become a reality. Pichchrhevaad ka khatra hai ki dwijvaad koh naashkar khasvaad jaise aghirvaad khada karna chahte hain’. Identity politics do not stop with the dominance of a particular caste because its orientation is always towards the narrowest possible identity.

20. India’s Affirmative Action policies have created a trap for its society as well as its polity.

21. Therefore, it is important to see that how this trap of identity can be dismantled. In the context of OBC reservations there is no time bar has been fixed, despite the fact that backwardness is not a fixed feature; it is a dynamic feature and changes over time. Therefore, in the absence of a duration cap, the castes which have been declared as backwards, will continue to be treated as backwards till eternity.

22. If the persons belonging to reserved category of castes are backward, they need to understand that it is not because sufficient percentage of reservation opportunities are not available. If this should be the case, then those castes which are not getting the benefits of the Reservation, must be the most backward.

23. The demand for caste census lack reasonability. As per available data, the incidence of backwardness is not as strongly linked with the phenomenon of caste as it is linked with regional or locational factors. It is a fact that people residing in rural areas are more likely to be backward and poor irrespective of their caste, compared with the people living in urban areas.

24. Today, after three decades, no sane minded person can claim that caste and class are the same as, in almost every caste, all categories of people, with various levels of developmental attainment, exist. Therefore, it is important that the government makes its stand clear on the issue of ‘caste’

25. In order to bring about a meaningful change in society, it is important to have good social intentions. No meaningful change can be brought about when the mind is filled with crudity. It appears that the members of the SBCCR had consumed an excess of the propaganda materials prepared during the British rule to control the people of India

26. People in general criticise the ruling dispensation of Bihar in the 1990s for lawlessness, or the so-called ‘jungle raj’. But, to be fair, the ruling dispensation cannot be singly blamed for such a condition. Whatever the then Government of Bihar was doing, it was not happening because of political recklessness; it was being done by design. Therefore, those who praise RSBCC and regard it as a great document, are morally wrong in criticising lawlessness, and the so called ‘jungle raj’ of Bihar. The ruling dispensation was just following and implementing the diktats and the social intentions expressed in the RSBCC.

27. Unfortunately, India’s current Affirmative Action policies draw their legitimacy from the ‘historical misdeeds’ argument. As a result, they continuously require ‘stories of supposed exploitation’ to be manufactured to keep them justified.

28. The irony of the ‘misdeeds’ theory is that it does not blame the dominant community and ruling establishments of the past; it blames a section of society which was also in a disadvantageous situation, and was fighting against its existential threat. When the whole of society was in a depressed and disadvantageous situation, and the question of survival was more crucial than any other question, it is difficult to believe that people would have indulged in various kinds of misdeeds against their own kind instead of defending themselves from foreign invaders.

29. As a matter of common sense, had the Indian social system exclusively benefited only a few sections of society and exploited the rest, it could not have survived thousands of years.

30. The persistence of the present form of the grouping of the castes is seriously hampering political justice as it appears more like a machination to banish members of the ungrouped castes from India’s political arena. The present situation is at odds with the Preamble of the Constitution as well as Article 14 of the Indian Constitution.

31. At present, India’s Affirmative Action policies are more an instrument of political mobilisation than drivers of inclusive development.

32. There is no ideational progression in the fundamental principles behind the policies despite the sea changes that have taken place over time in the situational factors.

33. As a result of the caste-wise identification of the backwards, caste regimentation was promoted, thus making social relationships conflictual. Forget development, this ushered in an era in which the maintenance of law and order — which is a primary necessity in a civilised society — became the big issue.

34. The purpose of affirmative action should be to make society developmentally inclusive. It should not act as a facilitator of the social and political domination of any caste or group of castes.

35. As per the census report of 2011, this difference between the rural literacy rate of SCs and the national rural literacy rate is 3.92 (62.85 SCs and 66.77 national rural literacy), is much lower than the difference between the rural and the urban areas — that is, 17.34 percent. This means that the development gap between the rural and the urban areas is much wider than the national rural literacy rate and SC’s rural literacy rate. This shows that the rural-urban divide is much wider than between two social groups.

36. The sub-categorisation of the caste will be helpful in making the distribution of the benefits fair in a limited way. It is the repetition of the same old mistake, but in a diluted form.

Recommendations of the Report

1. This Report recommends that the 50 percent ceiling, as decided by the apex court, should not be breached. After decades of Affirmative Action, even the continuity of the ceiling at 50 percent is a matter of concern, and raises serious issues regarding the effectiveness of the policies. After every ten years, the functioning of Affirmative Action policies should be assessed.

2. The first recommendation of this Report is to change the basis of the identification of the backwards. Among the many disabling factors, the locational factor, and not caste, is the most important determinant of backwardness, as available data amply shows.

3. This new category of backward classes of people will cover all the families/people living in the rural areas. However, as development status of the people differ, two categories have been created so that the neediest get the benefits of Affirmative Action policies on preferential basis. As far as family is concerned, the term ‘family’ includes the direct lineage of a person, such as father, grandfather, mother, and grandmother, etc.

The status of a ‘family’ has been considered a unit for conferring Reservation benefits in this Report, as it is a family which is forward or backward, rich or poor, educated or uneducated, all of which directly impact a person. Those families who fulfil all the above criteria should be given priority.

The two categories will consist of the following types of households/families, irrespective of their social identities.

Category I: Backward Households

1. Persons who live in rural areas

2. Persons who are not, or have not been, A & B class officers in any government — State or Central.

3. Persons who do not have a business whose annual turnover is more than 36 lakh Rupees

4. Persons who do not have movable properties worth more than 10 lakh Rupees

5. Persons of a family whose aggregate annual income is less than 8 lakh Rupees.

The above category should be regarded as an OBC category of people.

Category II: Most Backward Households

1. Persons who have less than two acres of tillage, or no tillage at all

2. Whose homestead is in less than 100 yards of land

3. Persons of a Family who have not taken the benefits of any kind of Reservation policies in getting government jobs or admission in an educational institution

4. Persons of those families in which no one has attained education up to the level of graduation.

5. Persons who do not have any kind of specialised skills.

6. Persons who do not have a movable asset worth more than one lakh Rupees.

7. Persons who are victims of other disabling factors, such as are handicapped, have no earning member in the family, are located in a geographically tough area, such as mountainous or other difficult areas.

Altogether twenty percent seats should be reserved for the people of both categories. Out of twenty, 10 percent should be reserved for the people of the Most Backward Households (MBH); and the rest 10 percent should be reserved for the people of Backward Households (BH).

4. While reserving seats in educational institutions and in government jobs, a ‘Minimum Criteria Clause’ should be included. The minimum cut off marks/grade of the general category of the people should be considered as the benchmark of selection in government jobs, or for admission in educational institutions for all categories of people. Alternatively, an independent, uniform, minimum criteria may be decided for all categories of people seeking the benefits of the Affirmative Action policies of the government. This recommendation is important to break the vicious circle of backwardness. Besides, it will remove the blot of being less efficient from the persons receiving the benefits of Affirmative Action policies. As a result, they will get better opportunities in private sector also.

5. There is also a need for the rationalisation of Reservation policies for the SCs and STs to make them just and appropriate. At present, 15 percent Reservation seats are for SCs at an all-India level, and 7.5 percent seats are reserved for 7.5 percent. Since a large number of SCs and STs families are still bereft of the benefits of the Reservation policies, it is recommended that, out of total 15 percent, 10 percent seats should be reserved for members of those families who have not received any Reservation benefits till now, and the rest 5 percent should be left for those families in whose family only one member has received the benefits of Reservation policies. Similarly, for the people of the ST category, 7.5 percent seats are reserved at an all-India level. Out of 7.5 percent, 5 percent should be reserved for those ST families who have not received any benefits of the government’s Reservation policies till now. And, the residual 2.5 percent should be reserved for the other people of the same category.

6. Mainly those people should be included in EWS category who live in notified urban areas but are facing various kinds of disabling factors. As far as Reservations for the EEWS category of people are concerned, they should be reduced to 7.5 percent from the current 10 percent seats reserved for them, in order to maintain a ceiling of fifty percent.

7. There is huge educational opportunity gap between urban and the rural areas. The establishment of equality is one of the cherished goals of the Indian Constitution, and education is the most effective instrument to obtain this goal. For this purpose, it is important that equal standards of education should be made available to all students. This warrants transformative initiatives by the government. Thus, it is recommended that the 9th to 12th standards of education should be fully taken over by the Central government, and the CBSE curriculum should be made mandatory for all schools, irrespective of urban and rural areas.

8. Identity based double benefits of Affirmative Actions should not be allowed. The Christian and Muslim communities are in an advantageous situation as compared to the deprived people of the majority community. Minority educational institutions are an important source of employment for the people of both communities, as they keep fifty percent of total seats reserved for the people of the respective minority communities. Besides, Muslim and Christian communities also have other kinds of institutional support from organisations such as the Minority Financial Corporation, the Waqf Board, etc. By virtue of being a part of internationally organised networks, they get massive external assistance, which is not available for the backward and deprived sections of the majority community.

9. The government may consider to use the ‘charm for the Caste’ for the welfare of the respective castes by channelising this energy in a creative way, if centrality of caste in Affirmative Actions policies continues to stay . At present, there are two social identities which are recognised by the government: caste identity and religious identity. There is a need for an equivalence of approach for both kinds of social identities. Therefore, formation of the Trusts and Societies associated with the welfare of a caste should be allowed and they need to be given the same status and autonomy which minority religion associated Trusts and Societies receive from the government. This approach may be called the ‘Uniform Welfare Approach’ (UWA).

10. At present, appointments in the government sector, or in semi government institutions, at the behest of the Affirmative Action policies of the government, are based on caste. Therefore, it is important to make a provision in which those who have received the benefits of Affirmative Action because of the backwardness of their respective castes, should pay back to their respective castes. For this purpose, a five percent tax should be imposed on the net salary (gross salary minus tax) of such persons, and the funds collected in this way should be distributed among the Trusts, Societies, and Associations working for the welfare of that particular caste, so that their caste also gets some advantage of their appointment.

11. At present, Affirmative Action policies are linked with caste, this has made them the fulcrum of political mobilisation. Moreover, there is a provision of caste-wise entry in the list of OBCs. However, there is no provision of caste-wise exit from the OBCs. This means a caste which was once categorised as a backward caste, will always remain a backward one. After the implementation of the recommendations of the Report of Second Backward Classes Commission — some castes have got political ascendance, and achieved political dominance. Such castes should be removed from the list of backward castes. In this regard, it is important to note that if a member of a caste has remained Chief Minister for ten years, and has adequate representation in legislative bodies, he should be removed from the list of backward castes. The continuance of such a caste in that list means that the politically dominant castes are being allowed to usurp opportunities which are meant for the deprived and politically weaker castes.

12. At present, there is no uniformity in the definition of creamy layers. This kind of discriminatory approach is not fair. There should be uniformity in definition of creamy layers for each reserved groups.